The Fraud God

The Fraud God

|

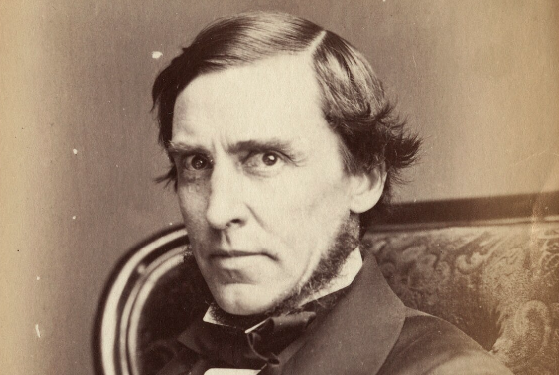

| James Anthony Froude 1860 Photographers: John & Charles Watkins (Source: UK National Portrait Gallery) |

I am currently reading the book Froudacity: West Indian Fables by J. A. Froude Explained by J. J. Thomas - a book written and published by Trinidadian author John Jacob Thomas in 1889.

|

| Front cover of Froudacity (1889) by J. J. Thomas (Source: British Library) |

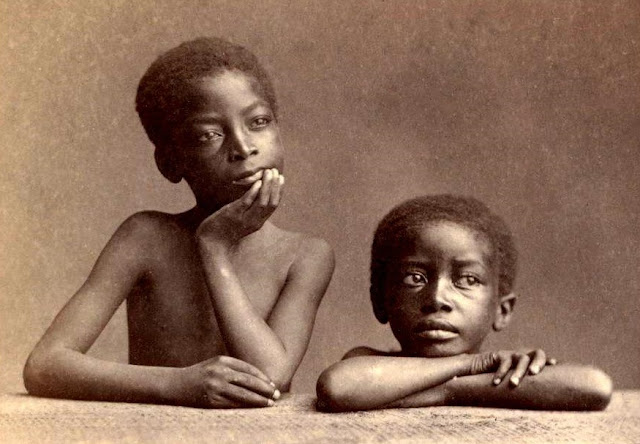

Thomas wrote the book as a response to James Anthony Froude's book The English in the West Indies, or The Bow of Ulysses, published the previous year. That book by Froude, an unapologetic racist and White supremacist, was full of lies about Blacks he observed while they were under British colonial rule in the Caribbean islands, especially in Trinidad.

|

| Front cover of The English in the West Indies (1888) by J. A. Froude (Credit: Nicholas Laughlin on Flickr) |

|

| Penelope Weeping Over the Bow of Ulysses 1779 Creator: Angelica Kauffmann (Source: The William Benton Museum of Art) |

Froude titled his book based on a Greek legend about a magical weapon owned by a king named Ulysses. This weapon was a bow that could kill three men with the shot of one arrow. One day, the king left his people on a long and dangerous quest to fight in a war against the Trojans. In his absence, the people of the kingdom presumed he had perished on the battlefield. His wife, Queen Penelope, decided to hold a competition for the successor to the throne. Whoever could string the bow of Ulysses would be the next king of Ithaca. Countless men near and far tried and failed to wield the mighty bow. There was not one who was found worthy. At last, Ulysses returned victorious and strung his bow once again.

|

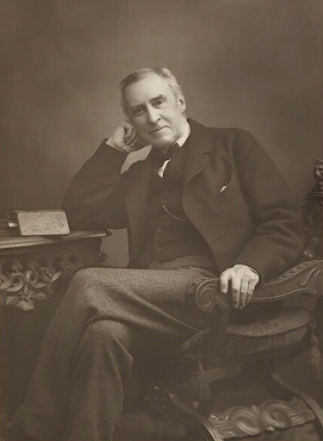

| James Anthony Froude 1890 Photographer: Walery (Source: UK National Portrait Gallery) |

Ulysses was a god among men. None was fit to rule the nation of Ithaca but the one called Ulysses. In the same way, Froude postulated that no Black people anywhere on planet Earth were capable of governing themselves independently of White people's supervision. The Black man, who had suffered in the White man's shadow for so many years, could not possibly wield the power that the White man created for himself. It was unfathomable for Black people to be anything more than a pitiful underclass and their greatest purpose on Earth was in working to sustain the dominance of a superior race. And who could be a higher authority on the subject than a man who traveled to each of the British colonies - in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and the West Indies - to see it all for himself?

I like how well Thomas dismantles Froude's work piece by piece. He examines every single claim made by Froude about the uselessness and helplessness of Black people and refutes them with hard facts.

In his own words, J. J. Thomas tells of his plight in writing this polemic:

"...I disregarded the bodily and mental obstacles that have beset and clouded my career during the last twelve years, and cheerfully undertook the task, stimulated thereto by what I thought weighty considerations. I saw that no representative of Her Majesty's Ethiopic West Indian subjects cared to come forward to perform this work in the more permanent shape that I felt to be not only desirable but essential for our self-vindication."

In the end, Froude was left exposed as nothing but a sham. Thomas, meanwhile, claimed his rightful place among the greatest writers in Caribbean history. Chike Jeffers of Dalhousie University and Peter Adamson, professor of philosophy at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich and at King's College London say of J. J. Thomas that his book Froudacity cemented his place as 'arguably the most prominent Black intellectual based in the English Caribbean in the 19th Century.'

I applaud Mr. Thomas. He took notice of the disrespect. But he did not just sit around and complain about it. He thought about what could be done. Then, he leapt into action.

Other educated and 'qualified men of our people' were 'fully satisfied' with the opinion columns blasting Froude's book in the local papers. But Thomas knew that something more needed to be done in order to bring these perspectives to a global audience in the same way that Froude conspired to do for his racist ideas. No one else was going to do it. So Thomas stepped up to the task.

"I deemed it a right and a patriotic duty to attempt the enterprise myself..."

Just think - what a different world would we have today if there were more people like Thomas to stand for what's right...men and women who are prepared to dedicate themselves towards a collective conscious and consistent effort in doing what is necessary for the progress of the people?

What a wonderful world that would be.

[Note: there is no known picture of Trinidadian writer John James Thomas. Thomas died just a few weeks after the publication of his book.]

Froudacity: West Indian Fables by J. A. Froude Explained by J. J. Thomas (1889) is available for online reading through the Digital Library of the Caribbean here.

- Omri C.

Comments

Post a Comment