The Things That Children Saw in Slavery

Everyone was a child under American slavery, but not all were "childish."

The Things That Children Saw in Slavery

|

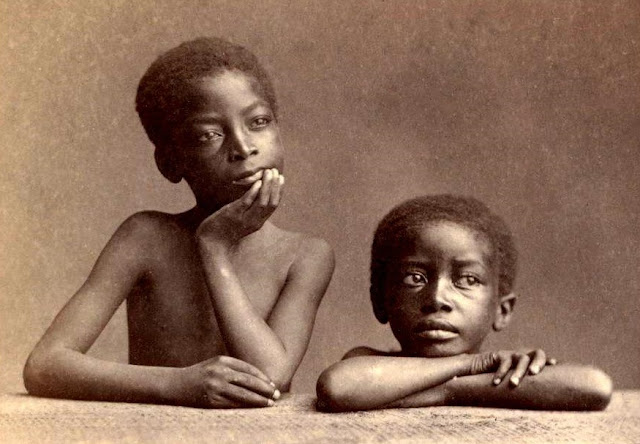

| "Black Angels" Charleston, South Carolina (Credit: Rob a.k.a. Okinawa Soba on Flickr) |

Many of the things that happened during the time of institutionalized chattel slavery in the United States were not spoken of or written down. But from what was recorded about this history, we can learn a great deal about the lives of enslaved African people.

The same holds true when researching the lives of children, who represented 25% of the enslaved population at the time of the Civil War.

Some of their stories survived with them into adulthood and were preserved in interviews with government workers and in books published on their behalf.

As the celebrated historian of the African diaspora, Sylviane Diouf, writes:

No person alive today can really know what it was like growing up as an enslaved child in the United States, but all these testimonies help form a picture of the kind of existence the children led.

From these stories, we can glean some information on the positive as well as the negative reminiscences of their lives.

The Story of Jim

In 1838, a 20-year-old Black man spoke to a White abolitionist about a former chapter of his life as a slave in South Carolina.

The narrative of this unnamed individual is one of the saddest stories of slavery that has ever been recorded.

Since then, Clemson University professor Susanna Ashton has uncovered the true identity of this man and verified details of his story by searching through newspapers, runaway ads, census data, and property records.

His name was Jim.

Until he was 14 years of age, Jim "belonged" to 'a widow woman named Smith' who hired him out to other masters.

One of these was an Isaac Bradwell.

While working for Bradwell, he happened upon something quite unsettling for any child to witness.

He saw slaves on another plantation being locked into wooden coffins in which they were suffocated for long periods of time.

I had frequently seen a very rich planter named Ned Broughton, pass his house going to Charleston, on horseback, before great six-horse wagons, loaded with cotton and indigo. He owned a great deal of River Swamp and made great crops. He punished his slaves by putting them into a long box just large enough to hold them, and then screwing a board made to fit into the box down on to them. The board had a hole in it for them to breathe through.

This man's wealth and the richness of his produce were no coincidence. They were a direct result of the way that he punished his slaves. As Jim would remark further on, the masters believed that the way slaves were "managed" was the primary determinant of how 'great' their crops would be.

Another one of the masters Jim worked for was a Mr. Smeth.

The master who lived next door to Mr. Smeth had an even more cruel way of punishing his slaves.

One day master sent me to his plantation on an errand, and I saw a man rolling another all over the yard in a barrel, something like a rice cask, through which he had driven shingle nails. It was made on purpose to roll slaves in. He was sitting on a block, laughing to hear the man's cries. The one who was rolling wanted to stop, but he told him if he did'nt [sic] roll him well he would give him a hundred lashes. Bellinger is dead now.

I can't imagine the pain that such a person might have experienced under this procedure.

This must have also been quite embarrassing for the one who was forced to inflict that punishment on their fellow man and, even more so, in the presence of a child.

While this incident stands out for its uniqueness among punishments recounted by survivors of slavery in the United States, it may not have been the most traumatizing of Jim's memories.

When he was sold to his second master, his mistress' oldest son Alfred, the tortures of other men, women, boys, and girls were suddenly up close and personal. His new mistress would use anything in her reach to punish the slaves - 'the tongs, or a knife, or anything she could get hold of.'

At this point in his narrative, Jim does not just describe the punishments themselves. He is careful to explain how he encountered these punishments.

One one occasion, Jim listened as the mistress punched and smacked her cook over and over while the poor woman had been forced to stand with her hands at her sides. After a while, the mistress picked up a large stick and continued to beat her with it. Jim says he was supposed to be raking leaves in the yard. There was no way he could have known these details unless he had been close enough to hear or to see what was happening.

At other times, he leaves no doubt as to his vantage point in these situations.

One day when I was watering the horses at the well near the kitchen, I heard a great noise, and in a few moments the cook woman Lucinda, came out with her head all bloody, so that you could not tell whether she had hair or not. Her head was all gashed up with a knife. When mistress found her head was bleeding all over the kitchen she sent her out to wash it off.--Bob Bradford of Sumpterville once jabbed a fork into a cook-woman and broke off the prong in her head, and his man Harry afterwards helped paddle her. I went there for salt, flour, coffee and sugar, and was there when he did it.

When a girl named Edith, who worked in the house, was accused of causing the mistress' daughter to stumble, young Jim was ordered to strip Edith naked and tie her to a table. He watched as the master whipped the child, then beat her with a paddle. After this was done, Jim had to clean up all of the blood, which had pooled around Edith, and scrub her lifeless body with salt water.

All through his book, we find eyewitness accounts of people being shot to death, whipped to death, or worked to death. Jim witnessed the deaths of other children as well.

The two places where most of these deaths occurred was on a main road and on a railroad which stretched from Charleston to Hamburg. In both these places, Jim says, the drivers 'were cutting and slashing all the time.'

It was after working on the railroad that Jim finally made good his escape to the northernmost state in the Union, abandoning all hope of seeing his family again.

To be quite honest, I have read many accounts of life in slavery. This story was, by far, the most daunting. And yet, Jim makes it very clear that there was a lot more he knew which he did not share.

It would take me a long time to tell about all the different kinds of punishment I have seen.

Professor Ashton identified the aforementioned 'Bellinger' as a man named William Cotesworth Bellinger Jr. (1788-1828), whose records match the time of death and the location that Jim described.

At the time that Jim's story was first told, some readers found it so disturbing that they actually questioned whether it was even true.

Earlier that same year, another widely published narrative of a slave driver in Alabama was challenged so heavily that the publisher was forced to discontinue it. The leading abolitionist paper wrote if off as false. The executive committee of the American Anti-Slavery Society, which sponsored the publication, concluded that the runaway who they helped escape to England gave them false testimonies.

When Jim's Recollections of Slavery by a Runaway Slave was published in the summer, members of the public responded with a similar wave of skepticism. The original manuscript was written anonymously by someone who sent it to a person with close connections to the editors of the Advocate of Freedom, based in Maine. The Emancipator, the official organ of the American Anti-Slavery Society, picked up the story, reprinting the first five articles that appeared in the Advocate and all subsequent materials.

With the growing popularity of Jim's story, the writers of the Advocate felt it necessary to make preparations for any challenges from the pro-slavery camp.

The following text appeared in both papers at the conclusion of Jim's narrative:

A few immaterial errors have been discovered by a close re-examination of the subject of the narrative, which will hereafter be corrected. The leading and material facts may however, we think, be relied upon with implicit confidence. At least such is the unhesitating opinion of all, who like ourselves have had the opportunity personally of questioning the narrator in respect to them. So far as the whippings and scourgings are concerned of which he so frequently speaks, the evidence on his own person is so strongly marked, as to satisfy, we presume, the most sceptical. It is intended to publish the narrative soon, in a pamphlet form, with such additions, corrections, notes, &c. as will best fit it for more general circulation. It may be made, we think, a very efficient plea for the slave, and our friends we hope will aid us in the effort to send it forth.

Should the narrative, through the medium of our paper, as by this time it may possibly have done, or in any other way, fall under the eye of any at the South, disposed to set up a claim for this piece of property, which has unceremoniously moved off, and became so suddenly changed into a thinking agent, abundantly able to take care of itself, we advise them to pocket the loss at once, with as good grace as they may, and to take no thought for its recovery. For, 1st. It is now in the possession of its right owner, and had better therefore remain where it is. 2. It has been so changed by its transfer to the North, as to make it a very unsafe thing on a southern plantation; for it has already very much increased its knowledge of geography, and has become somewhat initiated into the dangerous mysteries of reading and writing, and withal has learned to talk about liberty in strains fearfully contagious. 3. All attempts to recover it will be unavailing, and the expense therefore of the effort might as well be saved.

We wish our friends could all have the opportunity we enjoyed of hearing the story of this fugitive from the blessings of the patriarchal institution, from his own lips. It would not be necessary again, for one year at least, to exhort them to active, self-denying effort for the slave. The scarred back of the victim attesting the truthfulness of his story, his privations and sufferings in the house of bondage, the perilous escape, as he would tell of them--the joyful exclamation "but it is all over now, I am free, I am FREE!" would send a thrill through their hearts, that they would not forget to their dying hour, and lead them, as it led us, to repeat before High Heaven the vow, never to relax their efforts, until the whole system of vile oppression and wrong, by which millions of such are crushed in our land, is uprooted and destroyed. We wish that the doubters in immediate emancipation, might have the same opportunity.

While they acknowledged that establishing the victim's credibility was a necessary process in order for them to convince the public about the wrongs of slavery, the Advocate's editorial team made it clear that Jim's safety was of utmost concern. At this point, the best they could do to satisfy the question of Jim's authenticity was to provide a general description of his appearance and deportment.

They illustrated his scarred back.

Some of the scars are the size of a man's thumb, and appear as if pieces of flesh had been gouged out, and some are ridges or elevations of the flesh and skin. They could easily be felt through his clothing.

They further attested to his intelligence by saying that he was no longer 'a mere thing, a mere chattel' but 'a man, thinking, reasoning, working too, just like other men.'

A few months after the final installment of the series, a letter was sent to the staff at the Advocate, which they published for the benefit of their readers. In this letter, the writer claimed to have met with Jim and wrote that Jim was then employed on the same farm where he was working at the time that he first dictated the story.

We have more than enough proof to go on today. There is no doubt that Jim's story and the surviving stories of over 2,000 other Americans, who grew up in slavery, were real.

Professor Ashton's research team has identified Jim as a James Mathews, who was working on the City Poor Farm in Hollowell, Maine in 1850. This was not far from the headquarters of the Advocate. Matthews was also listed in city records as a patient at an insane asylum. Despite this, he lived through the Civil War and died in 1889. He was in his 70s.

It seems that Jim always remembered the exact location where he was when another slave was being punished on the plantation. This is very revealing about the impact that such scenes must have had on enslaved children. It indicates that Jim was in full fight-or-flight response. In each of these episodes of distress, his brain was focused on where he was in relation to the threat and where he might have been safe to run if he chose to.

In his narrative, Jim recalls the screams of the people who were whipped in his presence. He reflects on the approximate volume and on the patterns of blood they left behind - both on the trees they were strapped to and inside the buildings. He remembers the speed of his arm when he, too, was forced to partake in these punishments.

Modern studies have shown that repeated stresses in childhood can lead to problems later in life and I doubt that those memories of his childhood ever left him.

In the midst of Jim's narrative, we find a very conflicting statement:

Nobody can tell how badly the slaves are punished. They are treated worse than dumb beasts. Many a time I have gone into the swamp, and laid down and wished I was a dog, or dead...I have seen pretty tight times, but it's all over now I am free. I am mighty happy now. I am so glad, I can't sleep at night for thinking of it.

How can one be 'mighty happy' and 'so glad' and yet they are constantly losing sleep at nights for thinking about their freedom? It must then follow that Jim was still struggling from the mental anguish of his time in slavery. In the days, he was a free man, but at nights, he was reliving his experiences as a slave. Physically, he was free, but, mentally and emotionally, he was stressed out of his mind. His childhood trauma still had him wishing that he really had been born a dog and not a nigger. That trauma still had him contemplating his death, thinking that he really would have been better off if he had died a long time ago. His life, as captured by abolitionists in his time and by modern researchers, is consistent with that of a person suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). We may as well add to that a diagnosis of post-traumatic slave syndrome (PTSS).

What's more is that we do not read of any long-term intimate relationships in Jim's published story or in Ashton's research. Ashton writes that the people of Hollowell were Jim's adopted family. 'He was ill,' she notes, 'but cared for.' However, we must acknowledge that even with his youthfulness, his educational accomplishments, and a powerful work ethic, his adversities prevented him from a full enjoyment of his life in freedom. An early separation from his family prevented him from a family of his own.

In spite of all this, I would agree with Ashton in saying that Jim was scarred, but he wasn't scared. He never gave up and he never gave in. With no one to hold his hand or to wipe away his tears, he pressed on until he was finally free. In that, he is an example of the resilience of African people, who passed through so much - even as children - and kept on living.

On Jim's tombstone is only the simple phrase:

He hath done what he could.

The Story of Sam

Another narrative of slavery in South Carolina explored by Professor Ashton is that of Samuel Williams (1852-1946).

Sam's story is greatly contrasted with that of Jim. Sam writes fondly of his childhood memories. Unlike what we find in the majority of slave narratives, Sam's family was mostly intact during their time in slavery. He reflects on how happy he was playing with White children from around the community and learning how to read and write from local tutors (a group of White women who may have owned his father). He was just as proud following his master into the Confederate army at the age of 13 (as a body slave).

Sam considered himself one of the lucky ones.

In writing of his African ancestor, Clement, Sam noted:

His descendants up to the close of the Civil War, seemed with rare good fortune under the Providence of God, to have escaped many of the more cruel hardships incident to American slavery.

After the war, Sam was able to reunite with his entire family and they continued their new lives together in one household. Later on, he married for a second time and found a decent living to support his wife and five kids. Ashton tells us that Sam 'maintained good contact with many of his children and grandchildren' until his death at the age of 93.

Besides his own painful separation from his mother and two sisters, it would seem that Sam only knew of two instances in which physical abuse came to the enslaved.

One concerned a coachman named London, who lived with 400 other slaves on a plantation owned by a man with 'an ugly disposition' named Tom Bale. Sam visited Bale's plantation sometimes while living with his mother.

London and I were best friends, and so as to be on hand each morning when he went to the stable I was permitted to occupy a cot in his room, for I liked to go with him. He went much earlier than Uncle Ben. The poor fellow was glad to have me with him at night. It was a relief to him to have someone to talk to. He would tell me about the fine horses he had handled, and others he had known: Of Old Tar River, Bonnet so Blue and Clara Fisher. When he was seated on his box flourishing his whip with the easy grace of the experienced southern coachmen, one would not think his life was the terrible grind it really was.

One morning at a very early hour I heard Tom Bale calling from the yard, "London, London!" I tried to rouse the sleeping man without success. Presently I heard the heavy tread of his master coming upstairs.--And London slept!--The balmy air of that spring morning was seductive. The night had been rather warm and London was not encumbered with any superfluous clothing. Now London was very careful with his whips. They were not allowed to lay about carelessly, but were suspended from a rack of polished wood, made for the purpose, and hung against the wall in his room. There was one gold mounted, one mounted with silver, and one was adorned with carved ivory, one had a dainty little red ribbon bow on it, while the two others were decorated respectively with white and yellow.

Bale pushed open the door and strode into the room. He looked at the sleeping coachmen a moment, then, with a muttered imprecation, took down one of those whips; I don't know which. I heard the "swish" through the air, for by that time I had covered my head. Blow after blow descended upon him until the blood started. "Now," said the tyrant fairly exhausted, "Go down and hitch up my horse! I told you to have my buggy ready early this morning." The abused and bleeding Negro hastened to obey.

Sam described Bale as the only cruel master that he knew of personally.

It is more pleasant to me than otherwise that I have no other similar instance of cruelty to relate, coming under my own observation like that of Tom Bale's.

The second case of cruelty was not one that Sam saw, but one that he heard of from other slaves. In this case, a maid was caught by her mistress returning from a Black Methodist church, which she regularly attended on the weekends. The mistress, who was envious of the maid's homemade hat, forced her to burn it and to abandon all of the clothes that she had secretly designed for such occasions. This incident happened on a neighbor's plantation.

Sam remarked that this story 'may not be called cruel, still it is not devoid of severity and harshness.'

The relative simplicity of Sam's childhood might be due, in part, to the privilege attached to his notably lighter complexion and to the fact that his life revolved around the urban part of Charleston, where arduous labor in cotton and rice fields was not the norm.

Sam's narrative demonstrates that not all children were subject to extreme hardships under slavery in the U.S. South, but many of them were aware, to some extent, of the brutal treatment that others were made to suffer.

Still, Sam was not entirely unaffected by his experiences in slavery.

Slavery had more of a psychological impact on Sam.

Despite all that he saw and heard, he was a great apologist for Southern attitudes against Black people.

He wrote that to outsiders, the relations between White and Black Americans appear at best strained and at worst abusive, but that is only because the expressions and intentions of White Southerners are too often misunderstood.

In many parts of New England a very erroneous impression prevails regarding the attitude of the White people; I mean the White people of the South toward the Negro.

The general idea seems to be that the average southern White man sallies forth every morning with a bowie knife between his teeth, and the first Negro he meets, proceeds to lay him open in the back, broil him on a bed of hot coals and thus whet his appetite for breakfast. I found too, that this impression is largely the result of the thoughtless and altogether unnecessary talk of many Southerners visiting the North, who seem to feel it encumbent on them to disavow the very friendly relations that exist between these two races in many parts of the South, by expressions of indifference, and intolerance, that in many instances are never manifested at home.

The Northerners do not understand that these expressions are only meant in a sort of "Pickwickian" sense; hence the error.

Although Sam was anti-slavery, he asserted that when White Southerners said that they treat their slaves like they treat their animals, they usually meant it in a nice way. To Sam, there were only a few bad apples and they were far from the tree.

He also claimed that in all his 50 plus years of life, he had never been called a "nigger" by a White Southerner before.

Therefore, he reasoned, the insults and abuses that the South was known for could not have been as common they were said to be.

To the alleged few of his race, who did experience these slights, Sam invoked the Lord's prayer.

...Forgive those who trespass against us.

This is greatly contrasted by the words of Jim. Jim, who could not have passed for a White boy if he tried, wrote that he understood his treatment to be an injustice to him for which he was often tempted to retaliate.

I knew that I was wronged, and I have laid many a time and thought how to get revenge, but something always said "don't do it."

(Diouf points out that children saw the punishment of their family members as unnatural and in 'many' such cases, they did fight back.)

Jim also testified that the people of the South were far more cruel than those he found in the North.

The people here are different from what they are in Carolina. I like them a heap better.

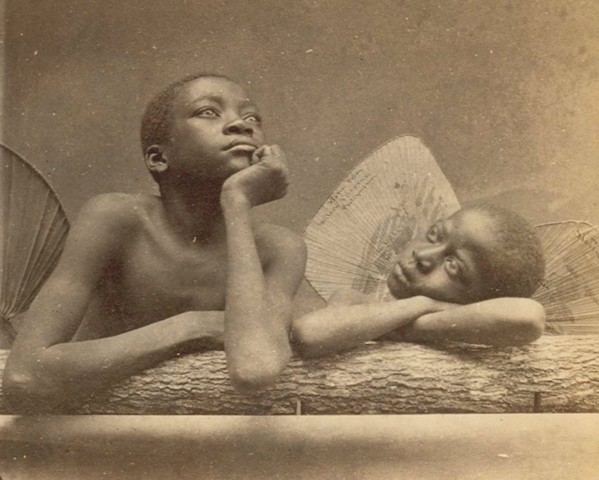

A Note on the Header Photo

The photograph of the two children was taken some time after the Civil War by George N. Barnard (1819-1902) and most likely at his studio in Charleston, South Carolina.

The caption on the back of the stereograph card in the collection of the New York Public Library reads: "South Carolina Cherubs - after Raphael."

|

| (Source: New York Public Library) |

|

| (Source: New York Public Library) |

This indicates that the photo was inspired by a work that the Italian Renaissance painter Raphael (1483-1520) made in 1513 or 1514 called The Sistine Madonna. That painting is now at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Gallery) in Dresden, Germany.

|

| The Cherubs (Source: The J. Paul Getty Museum) |

|

| Cherubs. (Source: New York Public Library) |

|

| The Cherubs. (Not) After Raphael. (Source: New York Public Library) |

- Omri C.

A special thanks to Deborah Y. D. Downey, the admin of the Lost Relatives group on Facebook, for her post presenting the connection in common between the artistic works of Havens and Barnard and that of Rafael.

For more on the life of Sam Williams, check out this digital exhibit by Professor Ashton:

https://ldhi.library.cofc.edu/exhibits/show/samuel-williams-and-his-world

You can also order Ashton's annotated edition of Sam's book Before the War and After the Union (1929) here.

To read more about the treatment of enslaved children in the United States, check out the book Growing Up in Slavery (2001) by Sylviane A. Diouf. It is available for checkout through the Internet Archive here.

Comments

Post a Comment