The Secret Savage

A slave-owner was only as savage as society knew them to be.

The Secret Savage

|

| William Byrd II (1674-1704) ca. 1700-1704 Artist: Sir Godfrey Kneller (Source: Encyclopedia Virginia) |

In my own estimation, Byrd was Thomas Jefferson before there was a Thomas Jefferson - the model of the American intelligentsia.

There were many striking similarities between the two. Both were born in Virginia. Both were raised into slave-owning families, inheriting both land and human "property" from their fathers. Both were "men of letters" and enjoyed reading Greek, Latin, and Hebrew literature. Both became fairly successful politicians.

Perhaps, the great difference between them was the contributions that Jefferson made to the establishment of the new government.

|

| Louis B. Wright as a member of the research staff at Huntington Library (Source: The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens) |

Bryd's notes were carefully written in code. Although they were first written in the early 1700s, it was not until the 1940s that they were transcribed into conventional English.

In his introduction to the first publication of Byrd's journals, Virginia librarian Louis Booker Wright (1899-1984) called Byrd 'the greatest gentleman of Virginia in his time.'

Almost every entry in his diaries follow the same format. Byrd writes that he woke up in the morning, then read his books, then said his prayers, then did his dance, then had his breakfast, then went to work on the state council, then went on a walk around the plantation, then went to his bed 'in good health, good thoughts, and good humor, thank Gold Almighty.'

On the surface, Byrd's work is the testament of an everyday genius.

His rigid routine evokes a strong desire to appropriate for himself an impenetrable persona of piety and propriety. In reality, Byrd's determined sophistry was nothing but an elaborate illusion. He would repent of his imperfections but he was proud of his transgressions. So zealous was he to appease his god with all his heart, soul, and mind that he consistently neglected the second commandment of love to his fellow man.

He calculated his every move. And yet, his writings expose another side of the equation. To his wife, he was a dishonest and disloyal control freak. To the enslaved plantation residents, he was a loose canon and an a--hole.

Byrd could hardly contain himself.

When he was not shouting down his wife, he was beating up his slaves.

He was beaming with joy when a cup of cold water met its intended target, drenching 'a Negro maid' who was passing beneath his kitchen window. He was proud to deliver a 'pint of piss' to his incontinent servant boy Eugene.

|

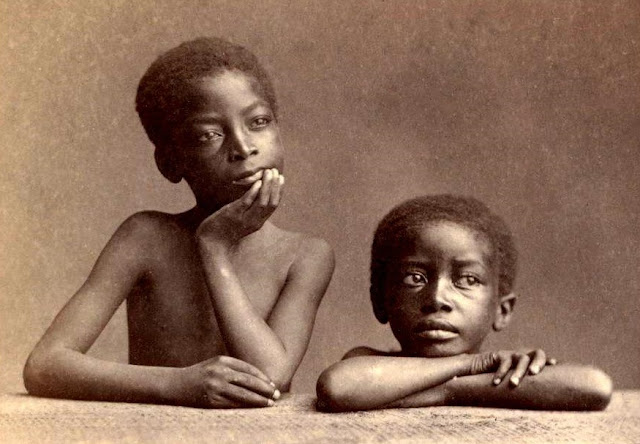

| Lucy Parke Byrd (1685-1716) with a young enslaved male attendant 1716 (Source: Colonial Virginia Portraits) |

With her 'violent and uncontrollable temper,' says Wright, she 'shocked her husband by the severity of her punishments.'

But her voice is largely absent in Byrd's narrative so we can only judge based on what her husband wrote.

Wright knew this well. He acknowledges this by noting that in detailing his arguments with his wife, Byrd was always 'careful to explain that she was at fault, and that he made the first move towards reconciliation.' Yet Byrd conveniently ignores the ways in which he triggered these tempers. After scandalously kissing another woman while at a ball, Byrd is remorseful about caving into what he called 'the lust I had for another man's wife,' but did not care much about the way he hurt his watching spouse. Each time she caught on to his escapades with the underage maiden, the mistress would torture poor Jenny and threaten the other slaves.

Byrd, meanwhile, was quite the gentleman.

Servants* were a particular trial, and the treatment they received was not altogether gentle, though sentimentalists may generalize too glibly about cruelty from incidents cited in the diary. Byrd clearly disliked punishing his slaves and often tried to get results by making threats. But occasionally he lost his temper—as well as the dignity one conventionally attributes to gentlemen—and in a fit of rage beat a servant. Once he whipped the cook for serving bacon half raw, and he kicked Prue, the maid, for lighting a candle in the daytime. He sometimes forgot himself so far as to quarrel undignifiedly with the servants.

What a gentleman!

When we read the actual words of Byrd, we find him in one place groping a Black member of room service at an inn - an attempt at rape which Wright says was 'unsuccessful.'

[October 6, 1709]

I rose at 6 o’clock and said my prayers and ate milk for breakfast. Then I proceeded to Williamsburg, where I found all well. I went to the capitol where I sent for the wench to clean my room and when I came I kissed her and felt her, for which God forgive me. Then I went to see the President, whom I found indisposed in his ears. I dined with him on beef on beef [nc]. Then we went to his house and played at piquet where Mr. Clayton came to us. We had much to do to get a bottle of French wine. About 10 o’clock I went to my lodgings. I had good health but wicked thoughts, God forgive me.

In other places, Byrd writes of his own housemaid...

[September 3, 1709]

In the afternoon I beat Jenny for throwing water on the couch. I took a walk to Mr. Harrison’s who told me he heard the peace was concluded in the last month.

[January 6, 1710]

I said my prayers and ate milk for breakfast. I beat Jenny severely. I danced my dance, and wrote a long letter to England.

[August 22, 1710]

In the evening, I had a severe quarrel with little Jenny and beat her too much for which I was sorry. I went into the river. I said a short prayer and had good health, good thoughts, and good humor, thanks be to God Almighty.

[October 11, 1711]

In the evening I took a walk and beat Jenny for being unmannerly.

Wright continues in his character analysis...

Byrd himself in a few instances meted out what seems to have been cruel punishment: he ordered a slave who pretended sickness to be fastened with a bit in his mouth, and later to be tied up by the leg; he sometimes had slaves whipped for laziness. Although the picture of the punishment of servants is not one that appeals to twentieth century humanitarians, Byrd’s slaves received far gentler treatment than that accorded sailors in the royal navy. By eighteenth century standards, the slaves at Westover were little less than spoiled. Certainly Byrd felt that he was a kindly master and inveighed in some of his letters against brutes who mistreat their slaves.

What an upstanding gentleman!

Historic Westover condemns racism. But ladies and gentlemen like the Byrds still gather today on the site of their plantation in Charles City, Virginia for parties and for weddings.

- Omri C.

|

| The Old Westover House 1869 Artist: Edward Lamson Henry (Source: U.S. National Gallery of Art) |

*It is important to note that the editors considered servants and slaves to be two distinct categories of workers - the former being Whites on a contract (indentured) and the latter being Blacks enslaved indefinitely. In Byrd's writings, it was not easy to identify a plantation worker as a slave or a servant. As Mrs. Byrd's portrait suggests, some of them were probably Native American.

The first and second transcriptions of William Byrd II's secret diaries are available for online checkouts through the Internet Archive.

For a deeper study on Byrd and his writings, check out the book The Commonplace Book of William Byrd II of Westover (2014) edited by Kevin Joel Berland, Jan Kirsten Gilliam, and Kenneth A. Lockridge.

Comments

Post a Comment