The Participation of African People in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

The Participation of African People in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

Slavery is a very serious and delicate topic for anyone to research.

To research and to present on the history of the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade is to undertake a task that can lead to a better understanding of the present situation facing the descendants of its victims and benefactors in our world today. But if a careful effort is not taken in this process, this same work can lead to negative consequences in our society. It can potentially spurn alternate histories, adding to the cadre of myths that are often presented as fact. A reckless approach to research on the history of the slave trade can make villains out of heroes and heroes out of villains.

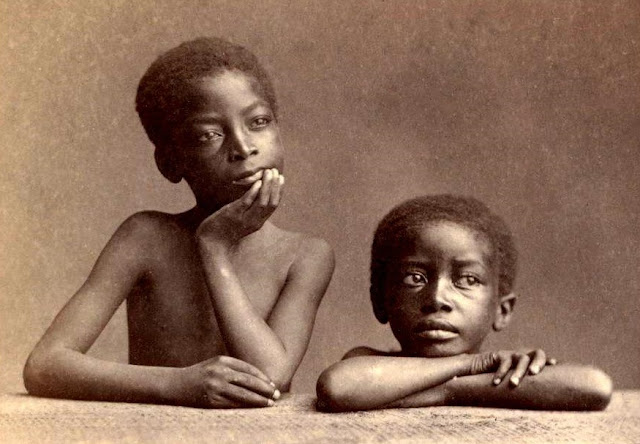

|

| From Hull Maritime Museum, Featured in A Pictorial History of the Slave Trade (1971) by Isabelle Aguet (Source: Slavery Images) |

In the "reflections" chapter of his massive 900-page Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade (1997), the culmination of many years spent in silent study, the best-selling author and leading British historian Hugh Thomas (1931-2017) remarked:

This large labor force would not have been available to the Europeans in the Americas without the cooperation of African kings, merchants, and noblemen. Those African rulers were, as a rule, neither bullied nor threatened into making these sales.

He acknowledged that there were cases in which 'some slaves were stolen by Europeans' and continued:

But most slaves carried from Africa between 1440 and 1870 were procured as a result of the Africans' interest in selling their neighbors, usually distant but sometimes close, and more rarely, their own people. "Man-stealing" accounted for the majority of slaves taken to the New World, and it was usually the responsibility of Africans.

For any casual researcher, it is easy to walk away from these statements with the belief that African people were the primary cause of their undoing and that Europeans had a very minimal role to play.

Thomas' rather indiscriminate view on the African side of this story - one that saw only a pitiful continent ravaged by cannibalistic palm-wine drinkers - was not lost on his compatriot Basil Davidson, who wrote these words in a review for the L.A. Times:

Hugh Thomas gives it with an admirable care for detail. This seems all the more praiseworthy in that he shows no evident interest in Africa's history or in Africans; but the slave trade saga nonetheless gets hold of him and will not let him go. And the captured reader, however disgusting the story in itself, is carried along with him.

...

Thomas, in short, has no curiosity for Africa's history and simply lifts the slave trade from that history as though it had no bearing on the matter.

Davidson warns us that Thomas is not alone in his condescending view of African history during this period.

Thus, we must exercise caution in our research - even as we learn from scholars in the modern era.

To this end, the study of a topic as great in its scope as African participation in the slave trade requires one to consult with sources representing as many perspectives as possible.

When I first looked into this topic, it was my belief that in order to satisfy the questions that I had, along with many others who have a similar interest in this story, I needed to be as transparent as could be with the materials that I was consulting with. A certain balance was also necessary. To piece together a history of African people that is fair and balanced is to center African people in both the narrative and in the commentary surrounding this subject.

To this end, I pulled primarily from the writings of victim Africans like Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (1705-1775), Olaudah Equiano (1745-1797), Ottobah Cugoano (1757-1791), Ignatius Sancho (c. 1729-1780), Broteer Furro (c. 1729-1805), and Venture Smith (c. 1729-1805) - all of whom were seized from the continent at the height of the slave trade. I also read from the stories of African people in our time and their journey to understanding the experiences of their ancestors in the slave trade. I would encourage anyone who wants to learn what African people had to say about the slave trade at that time, and in their own words, to find the narratives each of these individuals left behind and to read them.

|

| "Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African," Frontispiece of his Interesting Narrative (1791) (Source: Yale Center for British Art) |

|

| Portrait of Ignatius Sancho Frontispiece for his Letters (1783) (Source: Yale Center for British Art) |

|

| Detail of Cogoano From a portrait of Richard and Maria Cosway 1784 Artist: Richard Cosway (Source: Yale Center for British Art) |

As I hosted a series of research discussions on this subject, some crucial questions came to me, which I hope I can shed some more light on with this blog post.

For the purpose of convenience, this particular article consists, for the most part, of materials that I discovered very recently in my studies.

How Significant a Role Did African Opportunists Play in the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade?

British sea captain and slave trader William Snelgrave (1681-1743), wrote in 1734 that he hadn't the slightest idea about what the interior of Africa from the Windward Coast (modern-day Liberia and Ivory Coast) was like and he didn't know of anyone who had been there. Yet, he had sailed and 'traded to many places' with his father in West Africa since at least 1704!

In those places where I have been on shore myself, I could never obtain a satisfactory account from the natives of the inland parts. Nor did I ever meet with a White man that had been, or dared venture himself, up in the country; and believe, if any had attempted it, the Natives would have destroyed them...

At this point in the trade, the people here had decided that no White man was to enter their lands without their permission. All trade was to be conducted at sea. When a ship approached them, the natives would send a smoke signal from the shore and the Europeans would respond with another signal. Then, the natives would sail canoes to the ship and board with their wares of captives and ivory.

On the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), however, the British and the Dutch could boast of 'many...factories, under each of which is a Negroe Town protected by them.'

The reader may reasonably suppose, that here we might have a perfect account of the inland parts, but we can have no such thing. For the policy of the natives does not suffer White men to go up any great length into the country.

Again, in what is now Benin, 'no White man' was 'permitted' by the native people to travel more than '50 miles from the sea-side.'

British surgeon Alexander Falconbridge (c.1760-1791) made four voyages on slave ships between 1780 and 1787. In 1788, he published a book called An Account of the Slave Trade on the Coast of Africa.

In this book, he stated that Europeans were not always aware about how the slaves came to them.

There is great reason to believe, that most of the Negroes shipped off from the coast of Africa, are kidnapped. But the extreme care taken by the Black traders to prevent the Europeans from gaining any intelligence of their modes of proceeding; the great distance inland from whence the Negroes are brought; and our ignorance of their language (with which, very frequently, the black traders themselves are equally unacquainted), prevent our obtaining such information on this head as we could wish.

The path that Falconbridge traveled along the coast of Africa would have spanned a wide area from Nigeria to Angola.

I don't find it surprising that Black Africans could have prevented White Europeans for centuries from obtaining such information. Prior to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, European merchants were also kept ignorant of the location of Western salt fields and Southern gold mines so that only African people would have access to these resources. The reason was that such items would have depreciated in value if they were easy for everyone to obtain for themselves. Additionally, so long as African merchants could sell them exclusively, they could set and control the price of these items however they pleased.

In the absence of clear answers as to how African captives were being delivered to the traders, Falconbridge and his associates came up with their own theories.

Previous to my being in this employ I entertained a belief, as many others have done, that the kings and principal men bred Negroes for sale as we do cattle. During the different times I was in the country, I took no little pains to satisfy myself in this particular; but notwithstanding I made many inquires, I was not able to obtain the least intelligence of this being the case.

The information that Falconbridge was able to receive, he says, was occasionally told to him by captives on his ships (through translators) after he asked them questions pertaining to their capture. One man told him that he was pinned down by a large dog after he tried to leave a party that the slave traders threw for him. These dogs, says Falconbridge, were 'kept by many of the traders for that purpose.' Other stories revealed schemes that were not so elaborate. A pregnant woman was ambushed while returning home from a visit to her neighbors. A man and his son were 'seized by professed kidnappers' while planting yams in a field.

All the information I could procure confirms me in the belief that to kidnapping, and to crimes (and many of these fabricated as a pretext) the slave trade owes its chief support.

Falconbridge wrote that on one occasion, he witnessed a kidnapping with his very own eyes.

During my stay on the coast of Africa, I was an eye-witness of the following transaction: a Black trader invited a Negro, who resided a little way up the country, to come and see him. After the entertainment was over, the trader proposed to his guest, to treat him with a sight of one of the ships lying in the river. The unsuspicious countryman readily consented, and accompanied the trader in a canoe to the side of the ship, which he viewed with pleasure and astonishment. While he was thus employed, some Black traders on board, who appeared to be in the secret, leaped into the canoe, seized the unfortunate man, and dragging him into the ship, immediately sold him.

|

| Ambassadors of Soyo (a province of the kingdom of Kongo) who traveled to Recife, Brazil ca. 1637-1644 Artist: Albert Eeckhout Jagiellonian Library (Source: Annals of the Paulista Museum: History and Material Culture - Volume 25, Issue 2)* |

Several monarchs, who had established trade networks with Europeans in West and Central Africa, were complicit in the slave trade. The kingdom of Kongo sent several ambassadors to Brazil and Portugal to deliberate on the trade. These Africans 'set the terms' on how they would benefit in the process. In some cases, the king sent shipments of captives by the hundreds with them. 200 slaves were once received as a personal gift by then governor John Maurice (1604-1679). Brazilian historian Ana Lucia Araujo was able to identify at least five embassies sent to Brazil and to Portugal from the kingdom of Dahomey between 1750 and 1818. Male and female children were brought on these embassies as tokens of friendship. The last group in 1811 presented a slave girl to Portugal's King John VI (1767-1826), who was then Prince of Brazil.

Did African People Take Any Actions Against The People Who Were Exploiting Them?

Not everyone understood what was happening - that there was a system in place which relied upon the services of Black Africans to build the economies of White people in Europe and in the Americas.

Those who knew of the trade and were opposed to it had a limited capacity to intervene.

At times, they did, when they felt it was necessary in order to preserve their own communities.

|

| Arrest of Brue by order of the damel (king) of Cayor From Map Illustrations to be Used For the Voyages to Senegal (1802) (Source: National Library of France) |

In the summer of 1701, French slave trader André Brue (1654-1738) was captured by the ruler of Cayor in Northern Senegal and held for a ransom. But he was not just any old slave trader. Brue was appointed Director General of French Commerce in Senegal four years earlier. More specifically, he was the executive for the Compagnie Royale du Sénégal (The Royal Senegalese Company), which was a slave trading organization founded on behalf of the French government in 1673.

Brue had been building a factory on the river Gambia and colonial settlements in the interior of the mainland when Lat Sukaabe, the local ruler, had him arrested for 12 days.

It seems, according to Labat, that another king had been wrecking havoc in the land, making war on Sukaabe's kingdom and for some reason, Sukaabe decided that Brue was to blame.

In her book Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies (2003), historian of the African diaspora Sylviane Diouf profiles a number of cases in which African people resisted the destructive elements of the slave trade. African rulers, like Lat Sukaabe, who were altogether fed up with the system opposed the Europeans and their African allies by attacking slave castles or waging full-scale wars. Against this background, traveling to Africa for slaves was often a dangerous enterprise for European traders.

As the trade increased, so, too did violent revolts against the Europeans from continental Africans.

|

| Portrait of Jean Baptiste Léonard Durand Frontispiece to his Voyage au Senegal (1802) (Source: National Library of France) |

Durand noted that whenever a boat containing Africans approached a slave ship, the crew was put on high alert.

The crew is ordered to take up arms, the cannons are aimed, and the fuses are lighted. . . . One must, without any hesitation, shoot at them and not spare them. The loss of the vessel and the life of the crew are at stake.

Diouf, citing Durand, wrote that at one time, Fort Saint Joseph on the Senegal River was attacked and, as a result, all activities were stalled there for six years. A group of 'people' ransacked a dungeon in Sierra Leone where the infamous mulatto slave trader John Ormond held his captives before sale. In Upper Sierra Leone, Africans deserted domestic plantations and established 'maroon villages.'

The reason why there were so many defensive measures taken to secure European fortifications, says Diouf, was to prepare for threats both inside and outside. To emphasize her point, Diouf provides another quote from Durand, in which he stated that the colonial authorities were protecting themselves 'from the foreign vessels and from the Negroes living in the country.'

She also notes that more than 100 instances of Africans attacking slave ships from the land have been recorded, with 61 of these identified during the 17th and 18th centuries.

|

| View of Gorée, where a governor and several soldiers were killed during slave revolts; From Africa, containing a description of the manners and customs, with some historical particulars of the Moors of the Zahara, and of the Negro nations between the rivers Senegal and Gambia (1821) (Source: New York Pubic Library) |

However, African armies were not fighting the Europeans in order to save Africa.

Charles Testesole, the 22nd governor of Fort William, formerly located in modern-day Benin, was captured, tortured, and executed by the king of Dahomey in 1729. Prior to this, he had been appointed by the Royal African Company of England and served at that station for only four months.

Interestingly, Testesole was not punished for his cruelties to the slaves of that region, but for his cruelties to the slave traders of Dahomey. In particular, he whipped a Black trader and intimated that he would do the same to any other citizen of that kingdom, including his boss, the king.

In 1741, a Dahomean general launched an assault on a Portuguese fort at Whydah and his warriors put every man they met with to the sword. In the absence of the administrator, his stand-in (a Black man) sacrificed his life in kamikaze-style retaliation. Later on, the king rebuilt this fort for the Portuguese.

Both of these cases were highly political and both involved African interests in the slave trade.

King Adandozan of Dahomey complained to the Portuguese royal family in an 1810 letter about the way that their agent at the local Fort São João Baptista (Saint John the Baptist), Francisco Fe´lix de Souza (1754–1849), was hampering his own trade in slaves.

Because I confronted him, and asked him not to travel anymore to Popo, he started instructing the captains not to buy my captives, because they are all old and defective. As soon as a vessel arrives in Popo, this clerk starts walking around and gathering all the captives to sell...the clerk is the first to sell the captives and to open the market. He prevents the native people from doing business with these same captives.

In his letters, the king constantly referred to the Portuguese prince as his 'brother.'

To his dismay, his 'brother' failed to intervene, forcing Adandozan to take matters into his own hands. The king sent his army, who captured de Souza and dragged him to the Dahomean capital at Abomey, where he was imprisoned until Adandozan was overthrown by his youngest brother, Ghezo.

With all the firepower at their disposal, Europeans would have been well equipped to meet most cases of native aggression with a certain victory. (I recall reading of one trader who said as much.)

But they could afford to lose a few "good" men. Besides, there was too much at stake. If African people chose to withhold trade from the Europeans, then an entire industry would be in danger of collapse and with it, the Western would as they knew it. No slaves to till the lands of their colonies means no food and no clothing. Without a regular supply of slaves, they would starve and shiver. No slaves to mine their gold and silver means they would have very little with which to substantiate their wealth. No slaves to sell in Caribbean ports means no immediate funding with which to pay their workers and debtors. Such a dramatic shift would not simply result in the elimination of an entire social class but it could mean social upheaval as overzealous masters scramble to replace their gargantuan workforce.

African rulers understood the importance of slaves to the White men with whom they bargained. As far as possible, they leveraged their unique position of control over the supply chain to negotiate for armed protection from their military rivals and to agitate for increased prioritization over their economic competitors.

In the eyes of the White enslavers prowling the West coast, the kings of Dahomey - Adandozan and his father before him - were indispensable enablers of European commerce who ruled with an iron fist. As long as their empire continued to dominate, business was booming. And there were scarcely any hitches to expect from a transition of power. Upon taking the throne, Ghezo, like his predecessor, sold sympathizers of the former regime into the slave trade. Among these prisoners were members of his own family.

Dahomey was not going to let anyone boss them around. We see that the people of Dahomey were defiant and vengeful whenever they suffered any undesirable treatment from their European partners.

It is also worth noting that Dahomey did not need any help to accomplish these things. And even if they wanted help on these occasions, they would have been quite unlikely to find a willing ally. After all, they had made many enemies over the centuries, some of whose passions were primed before Europe entered the picture.

|

| Flag of conquest sent by King Adandozan to the Prince Regent of Brazil Dom João Carlos de Bragança National Museum of Brazil (Credit: Brazilian historian Ana Lucia Araujo) |

Plunder on the continent was the most immediate indignity of the trade that Africans encountered. Abuses at sea and in the diaspora were secondary. Whenever African people found themselves at the mercy of other Africans, they resisted with all their might. And African people, not Europeans, were the primary targets of this resistance.

Diouf tells us that just as the nations of Europe have warred over such things as 'land, religion, politics, influence, dynastic quarrels, expansion, economy, and territorial consolidation,' African peoples had conflicts for the same reasons. And just as European monarchs sent their criminals to their foreign colonies, African monarchs also sent prisoners away without a second thought for their survival.

On this point, Diouf remarked:

The English and French deportation policies did not elicit protest. There were no recorded attempts at freeing the convicts marching to the vessels bound for America and Australia, no assaults on ships to liberate the abducted, no moral outrage expressed at the evil of sending away other “whites” or brethren, no political attack on the institution of forced—quite distinct from voluntary—indenture itself, and virtually no rebellions on the ships.

This sentiment was shared by British slave trader Robert Norris (?-1791), who wrote:

The Africans have been in the practice, from time immemorial, of selling their countrymen, and never entertained any more doubt of their right to do so, than we do of sending delinquents to Botany Bay, or to Tyburn; deeming it fair and just to dispose of their slaves, prisoners of war, and felons, according to their own established laws and customs.

Along these same lines, Durand related this 'very curious speech' that a certain unnamed king of Dahomey was said to have delivered to a British governor and slave trader:

I admire the judgment of White men, but however skillful they may be, it seems that they have not yet sufficiently studied the nature of Blacks. The great Being created them all, and since he deemed it appropriate to distinguish them by the color of the complexion, we can presume different positions. There are also very important differences between the country [or countries] that we inhabit.

You, English, for example, you are said to be surrounded by the ocean and relate with the whole universe by the means of your vessels, while we, Dahomeans, surrounded as we are, can hope to obtain no such success of this between Negroes though rendered free. Freedom has nothing to do with it.

From various nations who speak differently than our tongues, we are forced to challenge ourselves and to punish depredations with the sword. This is how the wars are constantly being renewed among us, and those of your compatriots who claim that we then wage war to provide slaves for your ships, are grossly mistaken.

You think you can operate what you want to call a reform in the mores of Black people; but consider what a disproportion there is between the size of your country over there and the extent of Africa. You will soon be convinced of the difficulties you are experiencing in changing the system of a country as large as this one. We know that your nation is brave, and that you could bring a large number of Blacks to your opinion by the force of the bayonets; but for you to achieve it, that would have to be made into a large enterprise and [you would have] to commit various cruelties which are not customary among Whites, and these very means would be contrary to the principles of those who desire reform. I swear in the name of my ancestors and mine, that never a Dahomean engaged in war expeditions to obtain supplies [we had] to buy from your merchants.

Weibagah subjugated all his enemies.

Myself, who alone occupies the throne - not long ago, I have killed thousands of men without ever having conceived the idea of putting them up for sale, and assuredly I will kill many thousands more.

When justice and politics demand that men be destroyed, there is no silk, coral, or brandy which can take the place of the blood to be shed for the occasion.

Besides, if the Whites stopped frequenting Africa, would war cease on our continent? Certainly not; and if there are no vessels to bar us from the captives, what will be done with them?

You might ask me how Blacks will get hold of guns and powder. I will answer you by asking if they did not have clubs and arrows [before] having to know Europeans? Have you not seen me complete the customary annual ceremony in honor of Weibagah, the third king of Dahomey? Have you not observed that I carried a bow and a quiver filled with arrows, in memory of the custom of our ancestors? It is with such weapons that you could be very happy that you could have Blacks for your bayonets.

God made this world for war: - long ago, all kingdoms, large and small, even have practiced it in all times, although a slave to different principles.

Was Weibagah selling his slaves? No: he has always destroyed them without fate excepting a single one. And what could he have done with them? To let them subsist so that they could slaughter his subjects: that would have been a miserable affair. And certainly, if he had adopted them, the name of the Dahomeans would have been erased from the memory of men, instead of being, as has now become, the terror of other nations.

What especially annoys me is that some you wrote malicious lies in your books that never end. They say that we sell our wives and our children just to get us some brandy. We are unworthily slandered, and I hope that on my word you will contradict those scandalous tales that have been made about us, and you will teach posterity, that these imputations are wrong. We sell to the whites, it is true, some of our prisoners, and we have the right to do so. These prisoners - do they not belong to those who made them so? Are we to blame if we send our criminals to foreign lands? I was told you do the same.

(Loosely Translated)

Durand received this article secondhand and could not account for the authenticity of this speech.

But we do have the word of Dahomey's King Ghezo, who argued that the slave trade was intimately connected to the culture of his people and integral to their very survival.

In 1850, he resisted an appeal from Lieutenant Frederick E. Forbes of the British Royal Navy to end the trade, saying:

My people are a military people, male and female; my revenue is the proceeds of the sale of prisoners of war….. I cannot send the women to cultivate the soil, it would kill them…All my nation, all are soldiers. And the slave trade feeds them.

The kings of other conquering empires made similar statements.

Osei Bonsu of the Asante questioned the great and sudden aversion of European travelers to his staple commerce after their own governments banned the slave trade.

….the White men do not understand my country, or they would not say that the slave trade was bad. But if they think it bad now, why did they think it good before?

Invoking his religion, King Opubo Annie Pepple of Bonny believed that slavery was a divine right for his people. The trade, he said, was 'ordained by God himself.'

We think this trade must go on. That is the verdict of our oracle and the priests.

Africans were not one unified, homogenous population at the time of their early encounters with Europeans. The same remains true today.

Who Were The Captives?

|

| Colorized portrait of Jean-Baptiste Labat, derived from the new 2013 edition of his Nouveau voyage aux isles de l'Amerique (1722) (Source: Amazon/Kindle) |

Jean-Baptiste Labat (1663-1738), a French missionary and unapologetic slaveowner who lived in the Caribbean for a number of years, described the different types of people who were known to comprise the captives of Africa sold to the French. Based on this description, which he recorded in his 1722 Nouveau Voyage aux Isles Françoises de d' Amérique ("New Voyage to the French Isles of America"), these captives were mostly acquired by way of Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea (including Benin).

Labat outlined these groups as follows:

The first are criminals, and generally all those who deserve death or some other punishment.

The second are prisoners of war that they take [in wars] against their neighbors, with whom they are in constant war which has no other goal than these raids or kidnappings of persons, which they do by surprise, without ever arriving at an open war or a major action, or some decision.

The third are the personal slaves of the princes, or of those to whom the princes have given [slaves], who sell them according to their whim or need.

The fourth, finally, who are most numerous, are those that are taken, by order, by princely consent, by certain thieves called merchants who steal all the men, women, children they can catch and lead them to a vessel or the counter of the merchants to whom they must be delivered, who brand them immediately with a hot iron and put them in irons to be sure [they don't escape].

Jean Barbot, an agent for the Compagnie du Sénégal, kept two separate journals for his voyages to Africa in 1678 and 1681. In 1732 these were published under the title Description of the Coasts of North and South Guinea.

While historians have disputed its value as a historical source (and rightfully so), we can still find support for Labat's observations in this text.

Those Slaves sold by the Negroes, are for the most part Prisoners of War, taken either in fight or pursuit, or in the incursions they make into their Enemies Territories; others are stolen away by their own Country-Men, and some there are who will sell their own Children, Kindred or Neighbours. This has often been seen, and to compass it, they desire the Person they intend to sell, to help them in carrying something to the Factory by Way of Trade, and when there, the Person so deluded, not understanding the Language, is sold and delivered up as a Slave, notwithstanding all his Resistance and exclaiming against the Treachery.

How Did African Traders Treat Their Captives?

|

| View of the Village of Ben, in Cayor From Africa, containing a description of the manners and customs, with some historical particulars of the Moors of the Zahara, and of the Negro nations between the rivers Senegal and Gambia (1821) (Source: New York Public Library) |

The Afro-British abolitionists Equiano, Sancho, and Cogoano all condemned their fellow Africans for their role in kidnapping them, betraying them, destroying their human rights, and killing their family members (their words - not mine).

Diouf asserts that Cogoano's work was the only one out of twelve narratives she identified in which an African pointed to people of his own complexion as the perpetrators of their enslavement.

Then, in the statements that immediately follow, she dismisses that idea altogether.

Nowhere in the Africans’ testimonies is there any indication that they felt betrayed by people “the color of their own skin.” Their perspective was based on their worldview that recognized ethnic, political, and religious differences but not the modern concepts of a black race or African-ness.

True, each was specific in naming the ethnic group of their kidnappers when they could or certain traits that had nothing to do with racial categorization. Equiano was only old enough to recall 'two men and a woman.' Cogoano remembered them as 'great ruffians.'

Still, Equiano, Sancho, and Cogoano each conveyed and assented in their own ways to the common view of the racialized West that slavery in Africa was a process of betrayal.

Cogoano referred to 'the shame of my own countrymen.'

Sancho, who was born on the Middle Passage, wrote of 'the horrid cruelty and treachery of the petty kings.' Treachery literally means deception and betrayal.

Equiano, Sancho, and Cogoano also recognized that the Europeans were worse in their treatment of the African captives. Sancho adds that contact with European traders made the situation much more convoluted than it would have been otherwise.

We can find supporting examples in the testimony of outsiders like Falconbridge, who wrote that when a captive was deemed to be useless (basically if they were not purchased by the European merchants), then they were sometimes slaughtered in the sight of the merchants.

The traders frequently beat those Negroes which are objected to by the captains, and use them with great severity. It matters not whether they are refused on account of age, illness, deformity, or for any other reason. At New Calabar, in particular . . . the traders, when any of their Negroes have been objected to, dropped their canoes under the stern of the vessel, and instantly beheaded them, in sight of the captain.

|

| Carl Wadstrom and Prince Peter Panah who he redeemed from a slave ship in 1789 Artist: Carl Fredrik von Breda (Source: Nordic Museum) |

Some people survived rejection.

In her 2016 book Terror at Sea: Terror, Sex, and Sickness in the Middle Passage, Professor Sowande' M. Mustakeem relates the story of a time when Snelgrave declined an older woman, saying that she was beyond her useful years. The trader, claiming to be an aide to the king of Dahomey, insisted on behalf of his sovereign that Snelgrave buy the woman. He refused. Shortly afterwards, Snelgrave learned that this aide ordered the woman 'to be destroyed.' She was then taken away in a canoe, bound, and 'thrown as a sacrifice into the sea.' Later, Snelgrave retrieved a body from the water and discovered it to be the same woman. After some time, the woman reluctantly revealed to him, by way of translators, that the king had disposed of her for accommodating the women of the palace in forbidden love affairs.

One of the most brutal things that occurred on this leg of the trade was branding. But Europeans were not the only ones known to do this. Dutch trader Pieter de Marees reported that Africans branded their own slaves' shoulders on the Gold Coast in the early 1600s.

Once purchased, African merchants did not relent in their punishments on the captives.

As soon as the wretched Africans, purchased at the fairs, fall into the hands of the black traders, they experience an earnest of those dreadful sufferings which they are doomed in future to undergo.

Falconbridge wrote that even though the natives treated their captives very cruelly, captive Africans did not 'find their situation in the least amended' after they were transferred into European hands.

Their treatment is no less rigorous.

How Significant Was the Role That Foreign Opportunists Played in the Process?

In defending the slave trade against common claims made by abolitionists, Norris wrote in 1789 that the captives on slave ships were treated excellently.

On the voyage from Africa to the West Indies, the Negroes are well fed, comfortably lodged, and have every possible attention paid to their health, cleanliness, and convenience.

According to Norris, the facts cited by anti-slavery activists about how many Africans died on the ships 'had been exaggerated beyond the bounds of probability and truth.' They had sought 'to draw in glowing colors' an 'imaginary picture of human woe.'

He also stated that Europeans were not the ones doing the kidnapping.

The mode of obtaining Negro slaves in Africa, has been demonstrated to be in a way perfectly fair, and equitable; by a barter with the natives. The crime of kidnapping, as it is termed, with which the traders to Africa have been reproached, proves to be extremely unfrequent: for the African committee, whose business it is to take cognizance of such an offence, and for which the law inflicts a heavy penalty, have reported, that only one instance of it has come before them in the course of near forty years.

If anything, he believed the people of Africa were entirely responsible for their own situation. After all, they were a troublesome people by nature, quick to destroy each other for any reason they could find.

The turbulent and irascible disposition of a Negro prompts him to harass and dispute with his neighbour, upon the most trivial provocations. Lured by the love of plunder, before he ever saw an European commodity...

Thus, he insisted:

The wars which have always existed in Africa, have no connexion with the slave trade.

Norris, who had only really been to one small spot of land on a massive continent, claimed that all of the monarchs in Africa longed to expand their economies through trade and that the movement for abolition was only going to stifle social development in communities that were already corrupt and to prevent the ongoing "rescue" of millions who, if not for the trade, would be destined for a savage end in the hands of their captors.

Isabelle Auget, in her 1971 book A Pictorial History of the Slave Trade, wrote:

The defenders of the slave trade argued that African kings themselves were only too willing to sell their Negro subjects to White men. However, without buyers, there would have been no sellers.

There were abolitionists who said the same thing.

Cogoano was one of them, who said this verbatim.

Falconbridge was another. After meeting with Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846), a leading voice in the British antislavery movement, Falconbridge joined the Anti-Slavery Society and spoke out against the slave trade.

Falconbridge acknowledged that the reason these captives were being brought to the Europeans was because the Europeans were setting up shop on the coasts.

Speaking of an area off the coast of Angola, Falconbridge noted that during the five years before his arrival, when slave ships were scarce, Africans in that region were at peace with each other. As the traffic picked up, war increased as well.

The failure of the trade for that period, as far as we could learn, had no other effect than to restore peace and confidence among the natives, which, upon the arrival of ships, is immediately destroyed by the inducement then held forth in the purchase of slaves.

Granville Sharp (1735-1813), an pioneer of the abolitionist movement in England, disputed claims by apologists for the slave trade like Robert Norris, writing that a state of perpetual war did not appear in the early records of travelers to West Africa, but after the trade began to pick up.

|

| Granville Sharp, Esq 1805 Artist: Charles Turner © Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

It was long after the Portuguese had made a practice of violently forcing the natives of Africa into slavery, that we read of the different Negroe nations making war upon each other, and selling their captives. And probably this was not the case, till those bordering on the coast, who had been used to supply the vessels with necessaries, had become corrupted, by their intercourse with the Europeans, and were excited by drunkenness and avarice to join them in carrying on those wicked schemes; by which those unnatural wars were perpetrated; the inhabitants kept in continual alarms; the country laid waste, and as [British sailor] William Moor expresses it, infinite numbers sold into slavery; but that the Europeans are the principal cause of these devastations, is particularly evidenced by one, whose connection with the trade would rather induce him to represent it in the fairest colours, to wit, William Smith, the person sent in the year 1726, by the African company to survey their settlements; who, from the information he received of one of the factors [dealers], who had resided ten years in that country, says,

That the discerning natives account it their greatest unhappiness that they were ever visited by the Europeans.—That we Christians introduced the traffick of slaves, and that before our coming they lived in peace.

To further bolster his point, Sharp quoted from several slave traders, including Dutchman William Bosman and Englishman James Barbot, who both attested that a Dutch director at Elmina castle paid off a certain nation to attack the other nations around them, leading to a series of wars which depopulated that entire region.

Bosman, who worked as the chief merchant for the Dutch West India Company at Elmina, added that firearms and gunpowder were the top products in demand on native markets. These provisions from the European traders enabled the wars, which the natives were using for the purpose of obtaining gold and slaves they could trade to the Europeans for more weapons.

Brue, who himself incurred the wrath of the natives, wrote:

The Europeans were far from desiring to act as peace-makers amongst the Negroes, which would be acting contrary to their interest, since the greater the wars the more slaves were procured.

In describing the customs of the warring kings, Brue positioned the European merchants as the prime arbiters of chaos.

When a Vessel arrives, the King of the Country sends a Troop of Guards to some Village, which they surround; then seizing as many as they have Orders for, they bind them and send them away to the Ship, were the Ship's Mark being put upon them, they are hear'd of no more. They usually carry the Infants in Sacks, and gag the Men and Women for fear they should alarm the Villages, thro' which they are carried: For, says he, these Actions are never committed in the Villages near the Factories, which it is the King's Interest not to ruin, but in those up the Country.

Snelgrave called the land in what is now Benin the top destination in West Africa for slave traders from all over Europe.

It is no coincidence that King Guadja Trudo of Dahomey, who dominated in that region, was the greatest warmonger in that region. Dahomey wanted full control of the coastal trade and taxed the slave exports of their competitors. Those who refused to acknowledge Dahomean sovereignty were wiped off the map. Snelgrave recounted that when the conquering kingdom of Whydah heard the army of Dahomey approaching in 1727, the same valiant king and his people, who were then sending a thousand of their enemies into the New World every month, scattered to nearby swamplands, leaving everything behind. Then, one morning in the Dahomean camp, Snelgrave and his men were greeted by the sight of 4,000 Whydah heads. Soon afterwards, 1,800 captives of another country called "Tuffoe" were brought before them. 400 of these were slain and the remainder of them were appointed by the king as slaves, 'some for his own use; or to be sold to the Europeans.'

When the king asked Snelgrave what he wanted, Snelgrave's reply could be summarized in this statement:

Fill my ship with Negroes.

Even Snelgrave noted that in the span of 13 years from 1712 to 1725, the traffic of ships from the coast of England to the coast of Africa had jumped over 666% from 30 ships a year to more than 200. By this time, the English-sponsored Dahomey was in the peak of its power.

Merchants and traders were not alone in the business. Politicians and bankers funded their schemes with investments in the shipping companies. European kings and queens were scarcely isolated from these events. In fact, they chartered these very organizations and sent communications to African warlords on a regular basis.

It must be acknowledged that all throughout the trade, Europeans chose sides in the wars that Africans waged against their enemies just as they had done with the natives in the Americas. In the early part of the trade, European nations sent armies to fight alongside the African people. Citizens of Europe were enlisted as soldiers in these colonial armies. Later, European businessmen were adopted into African kingdoms as key decisionmakers - linguists, ambassadors, and even governors!

|

| Elizabeth Chandler Frontispiece to her Poetical Works (1836) (Source: The Library Company of Philadelphia) |

When Africa was removed from the equation, the role that the White masses in Europe and the Americas played in the continuation of African slavery became even more apparent to its opponents abroad.

Almost thirty years after trading with Africans for slaves was outlawed, Elizabeth Margaret Chandler (1807-1834) insisted that White Americans could end the domestic slave trade and all the horrors if they simply boycotted the slave-produced goods that slave-owners sold in the markets.

If there were no consumers of slave produce, there would be no slaves.

What Are The Takeaways?

Even after these facts have been presented to them, many have maintained the belief that White people were alone in the process of enslavement on the African continent.

Diouf makes it abundantly clear that a narrative that paints continental Africans as "sellouts" and one that says the only method of enslavement was for Europeans to bring Africans to their ships are equally wrong.

Africans on the continent did not think of themselves at this time as Africans or as Black people.

On the contrary, they recognized differences along ethnic and political lines.

The demand of European traders was the great catalyst for the slave trade. Rulers who were thirsty for power sent all who opposed them into the trade. Over time, they found that the more captives they supplied to traders from Europe was the more they received items they could use in wars of conquest. In an era of constant war, those with numbers on their side considered offense the best defense. But sometimes, that defense was not enough. Dahomey was almost destroyed by an army of "Eyoes" in 1738. It did not end there. For nine whole years, these "Eyoes" (probably Igbo people) terrorized Dahomey, burning, killing, and taking captives of the people.

Some groups formed alliances and others allowed refugees, displaced by the wars, to join them. But, generally, a third party did not interfere in the affairs of rival groups. It was every community for themselves and loyalties were forged within these social units. There were a number of reasons why African people responded in these ways to the impact of the trade on their communities. As Diouf says, their motives ranged at times from greed to utter boredom ("or indifference"). At other times, their motives were born out of concern and sincere generosity. They, too, were human after all.

African people living on the continent today are not the only ones wrapped up in this history. Africans across the diaspora are also descended from people who were very much involved in the conflicts that provided bodies for the slave trade. And being victims of these vices (abduction, exploitation, abuse, and even murder) has not excepted some of us from reproducing these and similar crimes.

So we must not condemn all Africans for the actions of a few.

Not all African communities were involved in the business of selling to Arabs and Europeans. Many on the continent are descended from people who were victimized. Some did not even have the capacity for defense and secluded themselves deep in the mountains. Not all who participated did so willingly. There is likely a small minority in that number. Some monarchs were bullied along the way. But I wouldn't be surprised to find that as in the United States, where less than 10% of people overall owned slaves while the privileged population they serviced benefited in the process, there were situations in which some communities who were not directly collaborating benefitted from the stability of larger neighbors who were and who effectually controlled their territory.

Hugh Thomas believed that Africans who were involved in the trade 'benefited greatly.'

While Europeans kept some Africans as slaves to help them manage the trade, many Africans were actually employed to to carry items for the traders, to guard the forts, to sail the captives from the shore, and to secure them on the ships.

To Africa's defense, Diouf submits that while Europeans were not known to launch any measures against the exile of their misfortunate and criminal classes, she found that 'many of these actions were recorded in Africa.' She also believes that while these defensive and offensive strategies didn't stop the slave trade, they led to reductions in the efficiency of African middlemen and thus, interrupted the supply of slaves to European markets.

I believe that in order to address much of the present inequities that resulted from this history, we first need to re-examine that history.

While materials outside of our reach are helpful in fostering a better understanding of our history, the decision-making process - taking actions based on that research - is a process that does not require outside intervention.

The parties most affected by this particular dynamic - Africans on the continent and across the diaspora - are also the most qualified to tackle the various issues associated with justice and restoration.

Someone mentioned to me during a conversation on social media that a team of researchers from the African continent and diaspora ought to travel and compile African testimonies in order to reconstruct the history of the slave trade and to determine the extent to which different tribes were involved before we can make any determination on African accountability.

I think that ultimately, based on my own personal experiences in research and presentation on this subject, we will have to acknowledge two key points and those are:

- For those in the diaspora, it will be a great challenge to find people who are serious about getting organized for such a task.

- For those on the continent, there will always be denial.

While official apologies have been issued from a few nations like Benin and Ghana, and from traditional rulers like those of Abomey in Benin and Bakou in Cameroon, there are many others who are not yet ready to acknowledge their historical role in the slave trade.

In Nigeria, for example, traditional leaders refused to apologize for the role of their people in 2009 on the grounds that any responsibility to do so lies only with the perpetrators and that slavery was 'very very legal' at that time.

This was the same view expressed by the reigning Queen of England, Elizabeth II several years earlier.

That process of refusal started long ago. In Benin, the name of Adandozan, who openly negotiated with Europeans on matters of trade, was effectually erased from the royal records of Dahomey.

I read a quote by British author Robin Walker someone shared to my Facebook group very recently that said:

History is any knowledge not acquired in the present.

Walker would be in the best position to clarify what he meant when he said this, but what I understand from this quote is that history is best studied from a perspective rooted in the time that is being studied.

We must recognize that a lot of knowledge about historical events as they occurred has been lost. In many cases, those who survived had some stake in the process of social upheaval. For example, to ask the descendants of traditional Dahomean rulers in Benin what happened to the other kingdoms is like asking the royal family of England what happened to the traditional rulers of Ireland.

Will they come out and say "we destroyed them of course"? Mmm...probably not.

And what about the rest of the indigenous population? Couldn't we ask them?

The people of Benin who were not Dahomeans, as they encountered Dahomey in the height of expansion, would have had a different memory of Dahomey than they do today. The same could be said for most of the dominant kingdoms in other African states and the smaller communities around them.

|

| A European cannon at the Royal Palaces of Abomey This was likely one of the cannons taken from the forts at Whydah. (Source: UNESCO) |

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the European colonial powers cut the heads off the snakes, so to speak, and afterwards, African people were taught to view only the Europeans as the ultimate conquerors of their lands and societies. In fact, Abomey, the old capital of Dahomey, continues in that region under ceremonial rulers. If we go back in time to the colonial period, we will find that the French government had effectually ended the traditional monarchy and replaced it with a puppet regime. There is only so much one can learn in that case.

That does not disqualify the descendants of the ruling families from delivering an accurate representation of their heritage (they do, in fact recognize the role they played). However, it does provide some context for us to understand that the perspective of the people in regards to the subject of slavery is shaped by a shameful history of collaboration and betrayal.

Some Africans deliberately chose to forget about what actually happened during the slave trade.

As a result, many in our time have never had the chance to learn about that history.

So while we may choose not to respect the plethora of sources that are available from the historical record, we must reckon with the realization that the alternative is not a perfect one either.

Colonial education in many places did not respect the oral history that African people had. African elders were not invited to teach the next generation. Rather, European customs and beliefs often took priority.

What percentage of the historical pool of grios survive today? How have their stories been shaped by social pressures - through 400+ years of intermittent conflict, when provoking the local rulers was a death sentence?

Many leaders of non-conforming and rebelling communities were sold.

We don't have eyewitnesses to hear from.

So there are a number of factors to consider.

Still, we are not without precedent. History professor Carolyn A. Brown, in her study of slavery in West Africa, found that in places where the population was more closely associated with the process of capture, the stories and cultural references to slavery are far more scarce compared to other places. However, she did find that in certain parts of Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea-Conakry, and Nigeria, where there was an open acknowledgement of this history, truth had survived the test of time. The record, as Diouf puts it, was 'not symbolic' but 'fact-based'. That record was not always in the form of a story, but was preserved in other ways as well such as in common expressions, in genealogies, in rituals, and in music. Brown's work is included in Diouf's book.

I believe a Truth and Reconciliation Commission would be a great start in finding answers to questions of accountability.

In order for us to survive and to prosper in this modern world, we need more unity among people of African heritage all around the world. If having a constructive discourse on our shared origins and on acknowledging the full history of socio-cultural and socio-economic separation (which has already drawn a great wedge between us) is going to bridge the gap and drive necessary changes that can lead to collective progress for all, I am all for it.

Of course, like everything, we have to start somewhere and hopefully, I have lent some energy to the cause with my research and reflections.

- Omri C.

*image added one day after initial posting

Comments

Post a Comment